GE15 : What we got right and the blind spots!

Voters started queuing as early as 7.40 am at the entrance of the Sultan Badlishah National High School Voting Centre on voting day for the 15th General Election (GE15) of the Padang Serai Parliament - BERNAMA

For General Election 15 (GE15) projections, EMIR Research based its estimates on public data, elections history and EMIR Research’s own data and models using a multi-technique approach.

Unquantifiable data is not easy to be included in intrinsically calculative election projection models in an objective and strictly non-partisan manner. However, these unquantifiable factors sometimes play the determining role leading to stunning upsets.

More stunning is that the EMIR Research was not alone in missing out on much stronger PN emergence from a blind spot or out of, as it is now branded, “new blue”—a phenomenon that deserves more attention and contemplation.

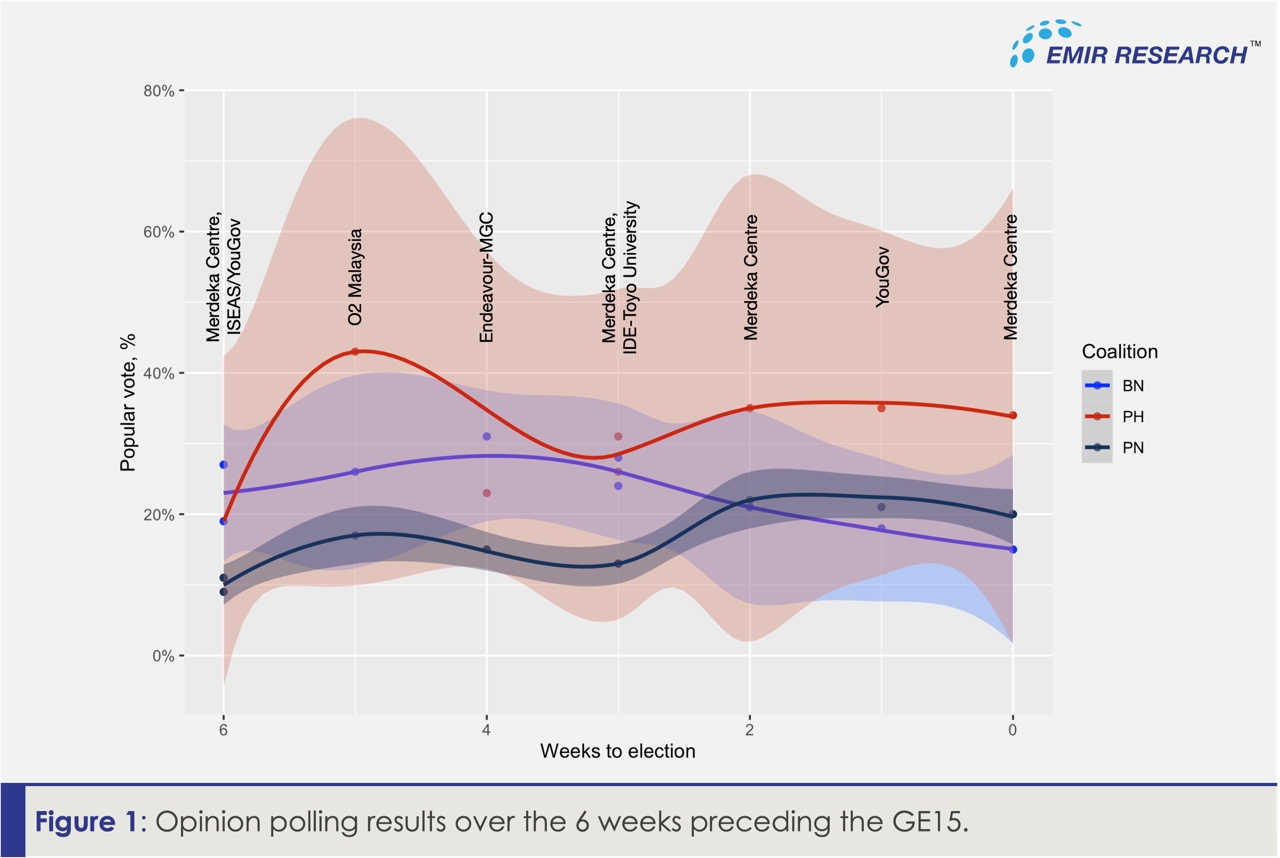

Note how the public opinion polls over the six weeks preceding the GE15 could not capture this dynamic (Figure 1). Only during the last two weeks before GE15, there has shown a very marginal prevalence (1% to 5%) of PN over BN popular vote. Even that, in strictly statistical terms, should be at best interpreted as a “no difference”.

Figure 1: Opinion polling results over the 6 weeks preceding the GE15

Interestingly, over the last two weeks, PH and BN poll-based popular vote hovered around its eventual outcome, while the projections for PN were significantly upset.

It appears there was an unquantifiable, yet powerful, nearly last-minute “underground” movement that was not easy to capture with the poll data unless being there in the field and carefully observing.

Meanwhile, the EMIR Research focused its projections on Peninsular Malaysia.

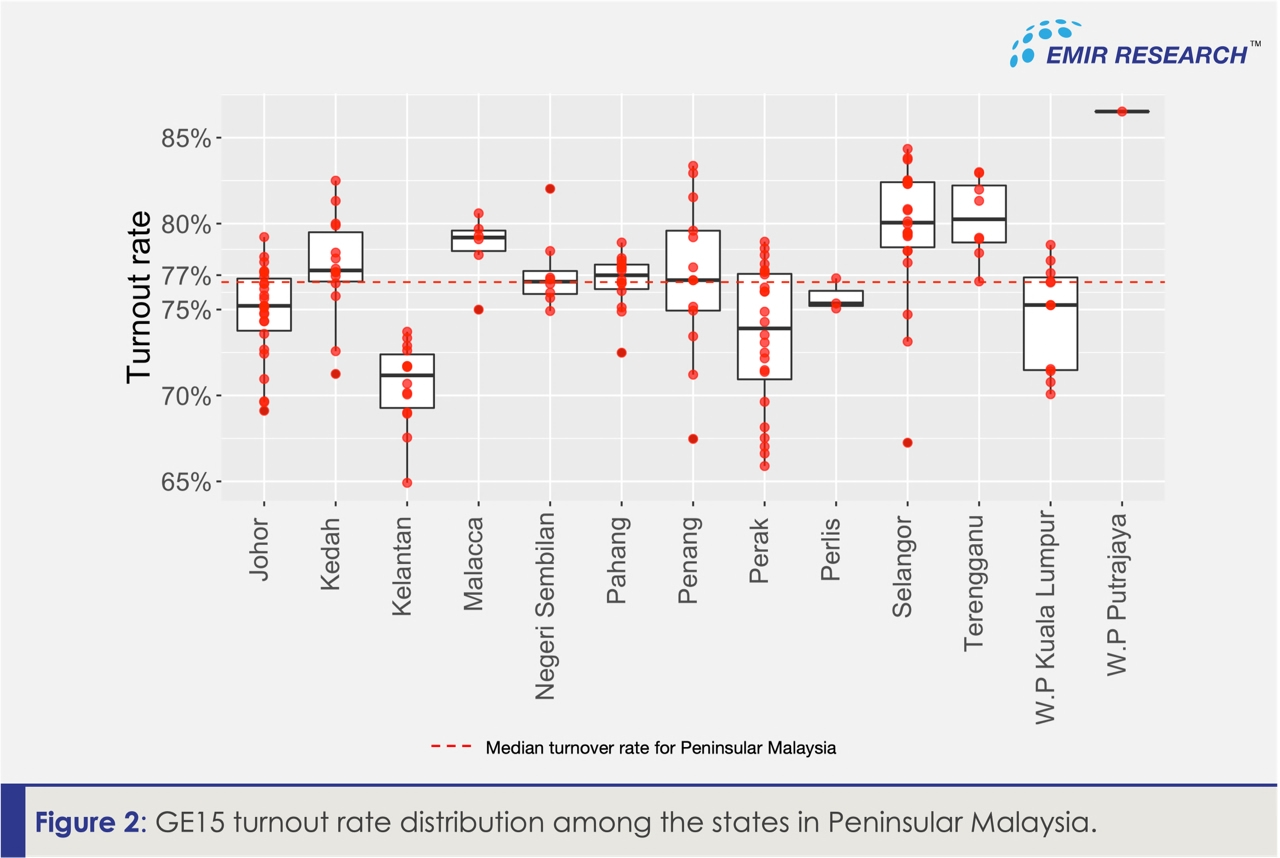

The projections were based on a median turnout rate of 77%— a spot-on parameter projection for Peninsular Malaysia (Figure 2).

Figure 2: GE15 turnout rate distribution among the states in Peninsular Malaysia

Out of 164 contested seats in Peninsular Malaysia, excluding Padang Serai, with a suspended election due to a candidate’s death, 111 were projected correctly. Another 22 seats were close-call projections. However, 31 parliamentary seats were ultimately not seen by the EMIR Research.

The unprojected winners were mainly PN (29 seats), while two others were PH seats. The misses were mainly between BN and PN and concentrated in the states of Kedah (6 seats), Kelantan (4 seats), Perak (5 seats), Pahang (4 seats) and Selangor (4 seats).

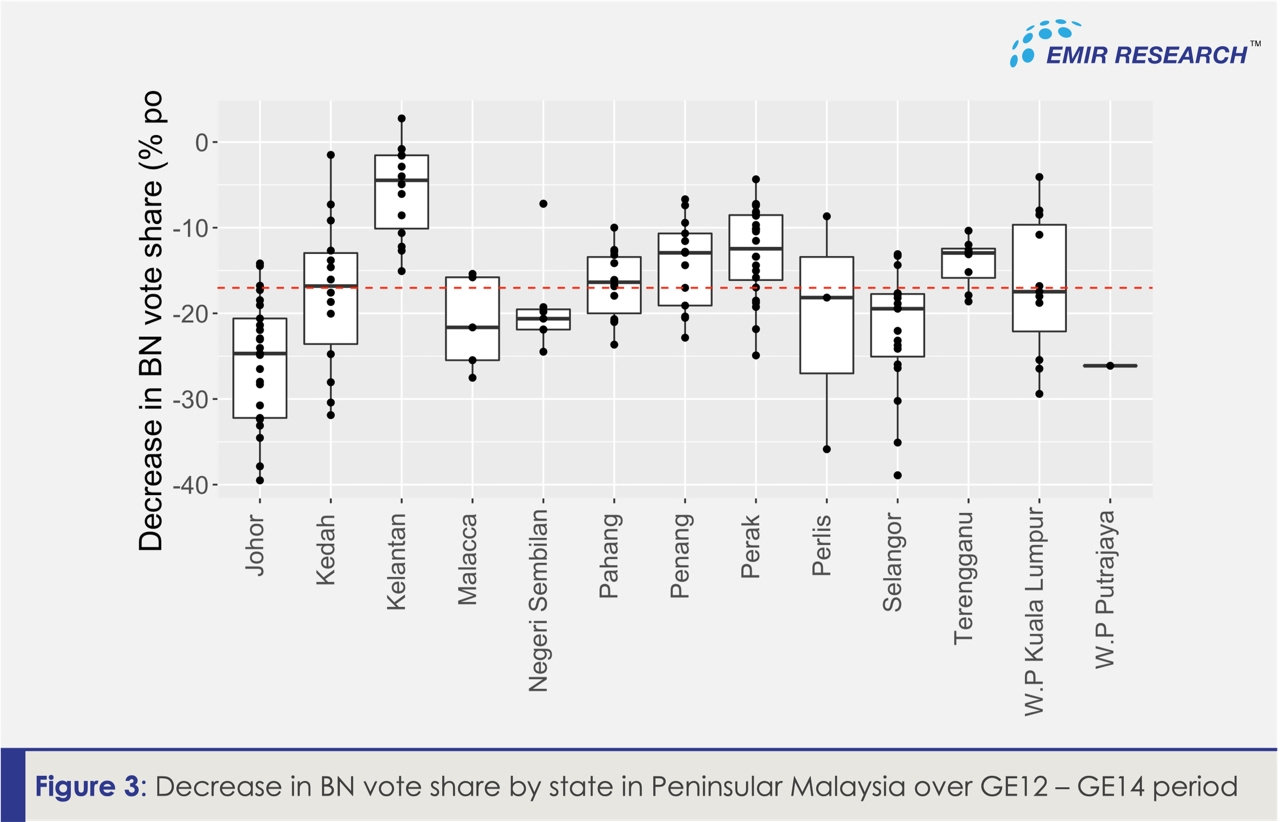

Note, that these same states, except Selangor, historically have demonstrated lower/slower erosion of BN share of votes over the period spanning the previous three GEs (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Decrease in BN vote share by state in Peninsular Malaysia over GE12 -GE14 period

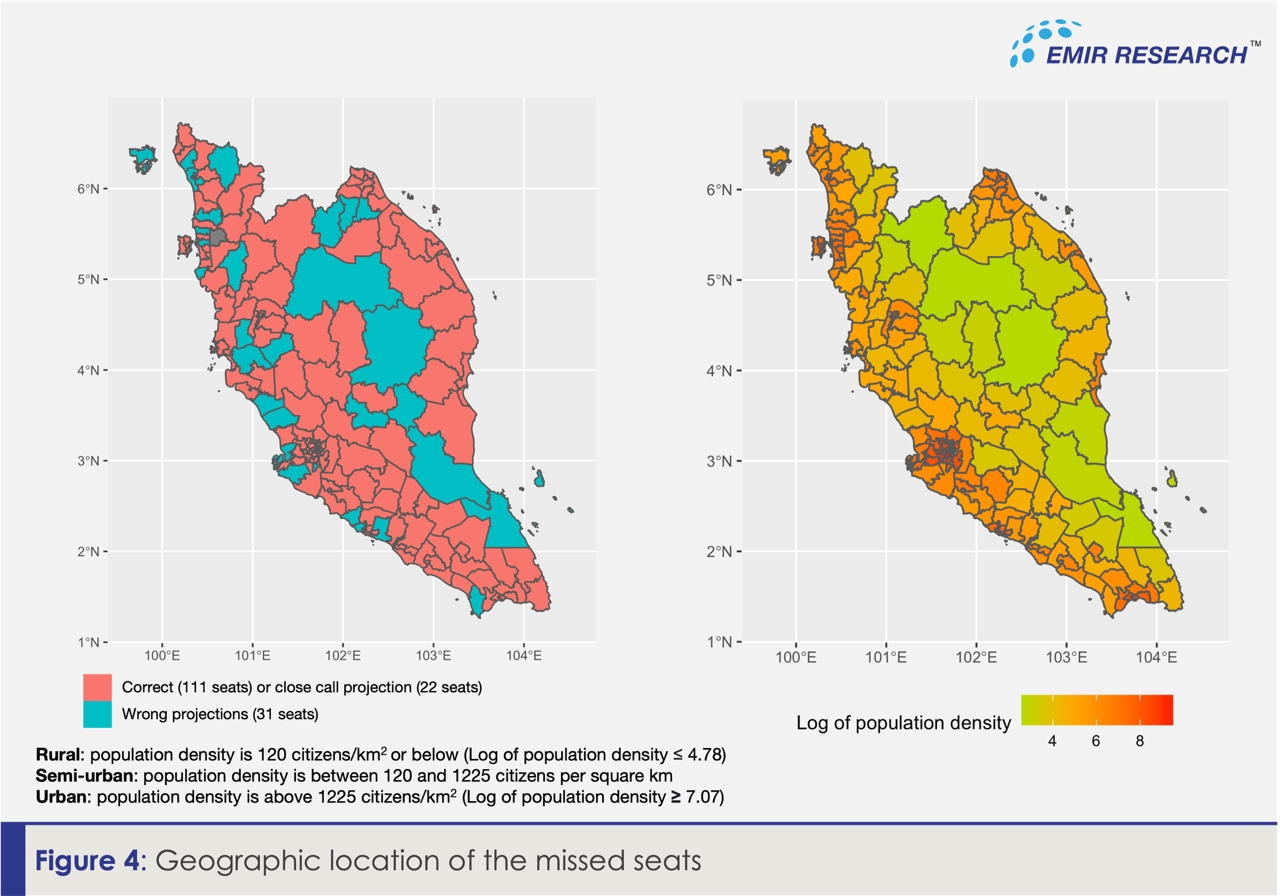

Notably, the missed seats were nearly entirely located in shallowly populated areas – geographically, “central belt” — mainly rural or semi-urban areas but on the lower side of the population density continuum (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Geographic location of the missed seats

The ethnic composition of the missed 31 seats is as follows: 28 Malay majority seats (70% and above Malay), out of which 9 have 90% and above Malays; 2 nominal Malay seats (from 50% to 70% Malay); and 1 relatively mixed (30% to 50% Malays).

Also, the seats projected by EMIR Research to be BN but won by PN (17 in total) are all Malay majority seats (8 are 90% Malays and above, 9 are 70% to 90% Malay) and mainly rural — 11 rural, 5 semi-urban and 1 urban (Putra Jaya).

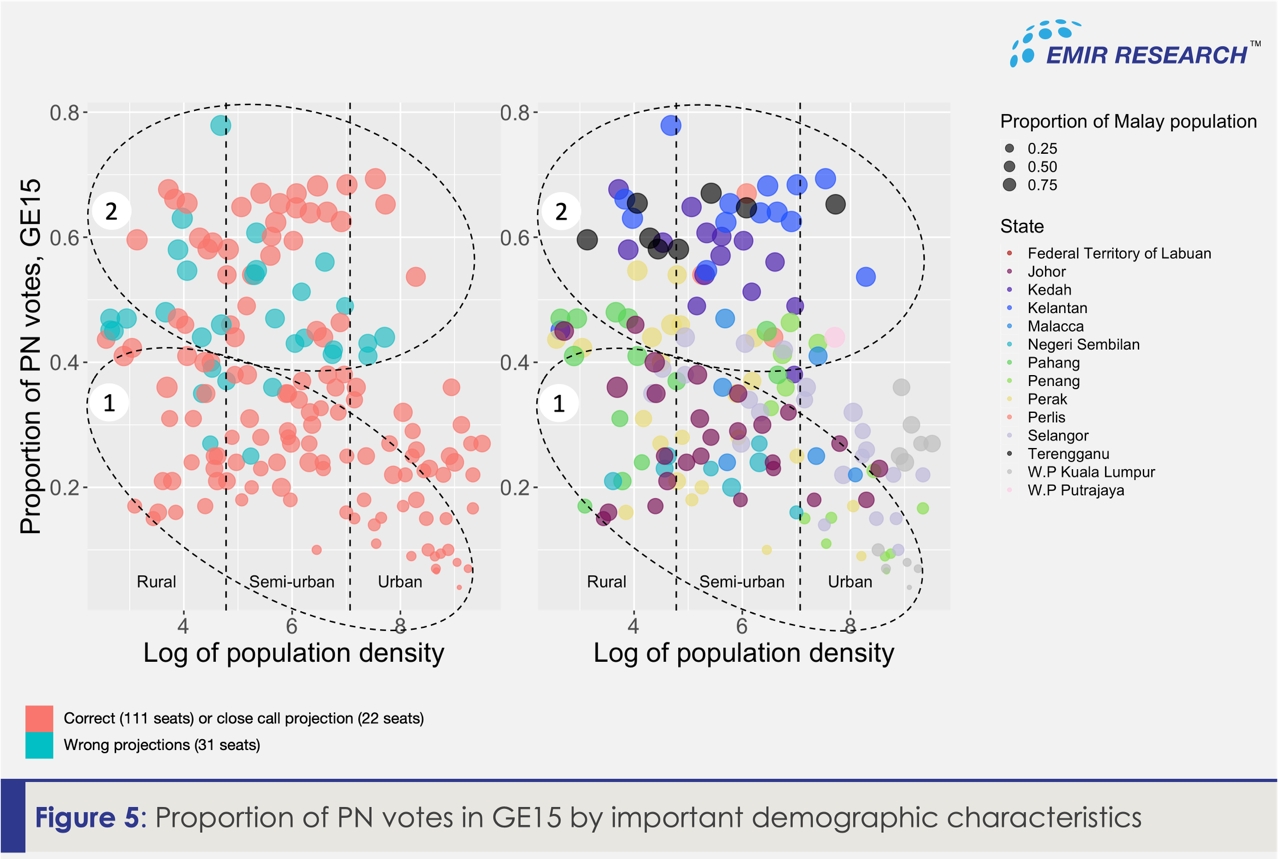

It is helpful to visualize the GE15 results by ethnic composition and domicile while focusing on the PN share of votes (Figure 5). This is where we can notice the emergence of two clusters (highlighted with dashed contours in Figure 5).

Figure 5: Proportion of PN votes in GE15 by important demographic characteristics

Within the first cluster, the distribution of support for PN follows the well-familiar pattern (like that observed for BN in the previous elections) — the share of support drops significantly in a linear fashion while moving from very rural to semi-urban and eventually to urban areas paralleled by the decreasing proportion of the Malay population.

However, in Figure 5, we also notice second cluster where the pattern kind of breaks, and we observe extremely robust support for PN irrespective of urban-rural domicile. All the seats in this second cluster are Malay majority, and they are mainly constrained to the states of Kedah, Kelantan, Terengganu and some rural and semi-urban parts of Perak and Pahang.

The 31 seats missed by EMIR Research were mainly located in this second cluster and, as was earlier emphasized, almost entirely concentrated in the areas with low population density.

This distinctive pattern suggests that this second cluster (Figure 5) might be skillfully targeted in ultra-Ethno-nationalist political campaigns resulting in those unquantifiable, powerful and, probably, last-minute dynamics — not an uncommon phenomenon in our reality where social media and emotions drive individual choices that can be shaped last minute.

EMOTIONS OVER RATIONALITY

The identity-politics-charged emotional appeal of PN campaigns was indeed extremely strong. However, we must remember that a rational mind does not generate a charge strong enough for an action, especially within a short time frame. That requires time and cognitive effort.

However, and unfortunately, a significant number of voters in predominantly rural areas lack political sophistication and are, at least, cognitive misers (exhibit a tendency to think and solve problems in simpler and less effortful ways rather than in more sophisticated and effortful ways), if not outright lacking a clear representation about the depth of socio-economic issues faced by the nation.

To galvanize this crowd, the PN needed not reinvent the wheel. They only needed to fan an old and already well entrenched in these localities Umno’s narrative, while, at the same time, differentiating itself from Umno only on one parameter – public perception as being clean from corruption and therefore a better “protector of Malays”— in the best traditions of keeping it simple, stupid... unsophisticated.

The seven years were long enough for the idea of Umno having four-stage cancer in terms of corruption and abuse of power to finally sink into this crowd's minds. So PN simply masterfully knocked out the cork of a vessel with an emotional charge of unexpressed anger and disgust and pointed towards the way to release it. At the same time, PH’s (including MUDA’s) more rational campaigns taking it to the core reasons why our nation is currently in such a miserable state would, unfortunately, not ring a bell to this audience.

The emotion of fear and displacement or losing “privileges” was too strong. Not many of these cognitive misers could decipher what those “privileges” really mean – the ability to hold posts in few job sectors, most of which are low paid (except for minority few) and from time to time receive “hand-outs” which are far inferior to offset the negative impact of the overall economic decline experienced by our nation over the last 20 years and predominantly deteriorating conditions specifically in Malay overall and rural communities (for detailed supporting figures refer “Ruthless colonization Mat Kilau could not even imagine”).

Not many of them could discern that, ironically, it was PN’s overwhelming focus on handouts, albeit necessary at that time, combined though with sheer inaction and disinclination to advance structural reforms in the areas such as social safety net, high-paid job creation and food security that seriously exacerbated Malaysia’s weakness as a whole and particularly within these vulnerable groups.

It would also require a certain cognitive effort to see how disgusting identity politics serve as the primary life force of corruption on a national level (see “Identity politics and corruption: Twin evils”).

However, PN’s political campaign invigorating precisely this shadow force was too sleek and targeted.

UNSOPHISTICATED YOUTH

On another end, PAS was gearing its TikTok campaigns by pulling the religion trump card, which the youth in the east coast rural areas would easily digest. Forget not that most of the kindergardens in rural areas are run by PAS, which gives them immense opportunity to leverage years and years of youth indoctrination and feeding on a diet of PAS’s ideas and slogans.

In general, PH’s campaigns appear to fail in appealing to the youth, while those under 30s commanded 28% of the electorate in GE15, according to descriptive statistics presented by ISEAS (“Malaysia’s 15th General Election – Results and Analysis”).

It is reasonable to expect young voters to be disconnected from the entire history of the reformasi era and Anwar Ibrahim’s struggle, but what was fresh in their memory is PN’s handouts during the pandemic.

On the youth front, only MUDA was fighting the battle, including on social media. However, again the rational, logical, and practical appeal, in the best-case scenario, would probably be cut out mainly for the urban youth. Even this is in case if they happen to read beyond the “handouts” in coreless manifestos of PN and BN (see “Look beyond the veil of empty promises and handouts”).

MONEY POLITICS

In the same vein, in the best traditions of Umno/BN, PN’s efforts were focused on “last-minute distribution of handouts and goodies”.

According to Bridget Welsh, based on interviews across Malaysia, in rural communities in Peninsular Malaysia, or remote areas in Borneo, “a theme” was clear: “voters are waiting for funds to come down.”

And PN obviously had the most prominent funds to be spent in GE15 campaigns, as was numerously highlighted by various political analysts, observers and researchers who have done fieldwork on the ground. Undeniably PN had the most visibility on mass media, and they massively deployed social media with its power of “influencers”.

PN’s resource advantage also poised the party to gain through the last-minute use of resources. While the call to prevent using phones in ballots booths could have dampened the vote buying, the importance and history of this practice in Malaysia should not be underestimated. The rules might be there, but the question is always whether there will be adequate enforcement. And, in a corruption-ridden country, enforcement is merely a joke.

Overall, quite a parallel can be drawn to the 2016 US presidential election, when despite most polls predicting Hillary Clinton as a leading candidate, Donald Trump, against all odds, clinched the presidency. This is mainly because Hillary’s message, however rational, practical and agreeable to many, still failed to generate enough group excitement to carry her to the finish line.

Nevertheless, Malaysia has a new government. Together with it, there is a new hope that this government could deliver on its high promise to prove how our multi-ethnic, multi-religious and multi-cultural society can flourish as one under the governance systems with strong and transparent institutions and a high level of coordination between social policies (need-based, focussed on many) and industrial policies (merit-based) as this is all that it should take to finally defeat the fear-mongering that for decades held our country in tenacious grip of twin evils — the identity-politics and corruption.

Rais Hussin is the President and Chief Executive Officer of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.

Must-Watch Video

Stay updated with our news